The Chieming-Stöttham archeological excavation – comments on a recently published article

by Chiemgau Impact Research Team (CIRT)

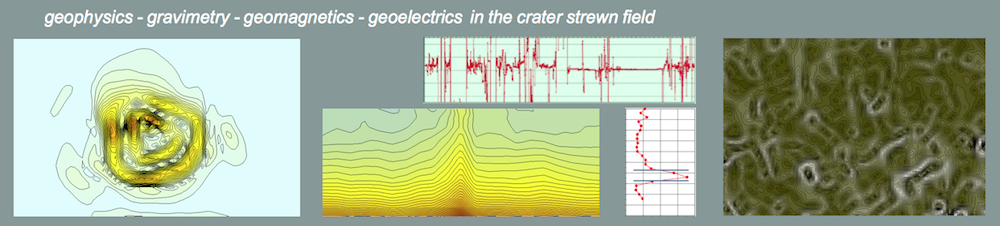

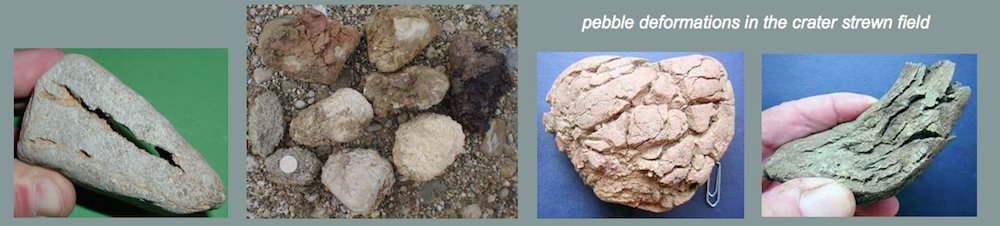

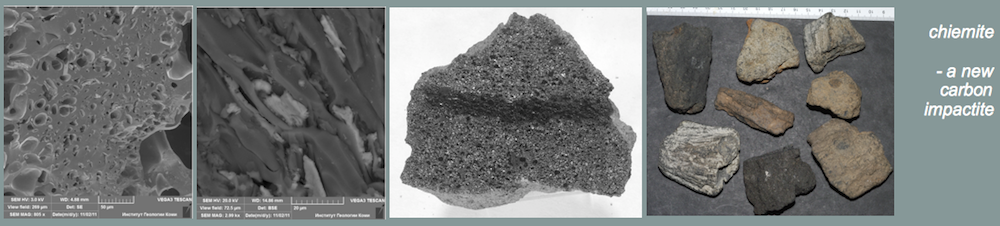

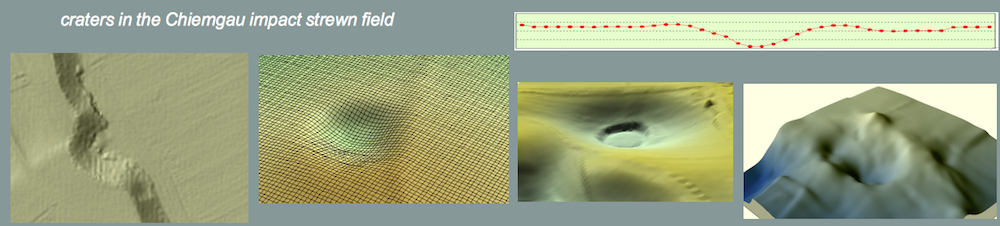

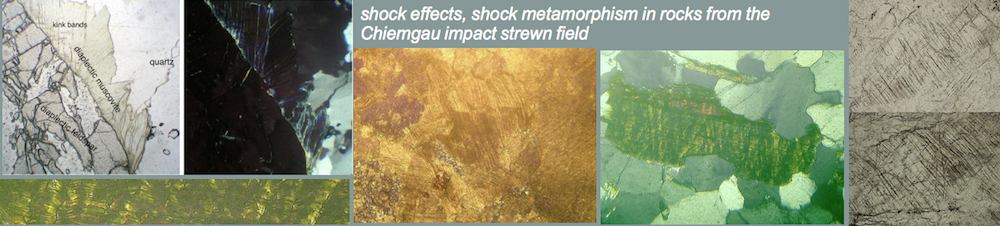

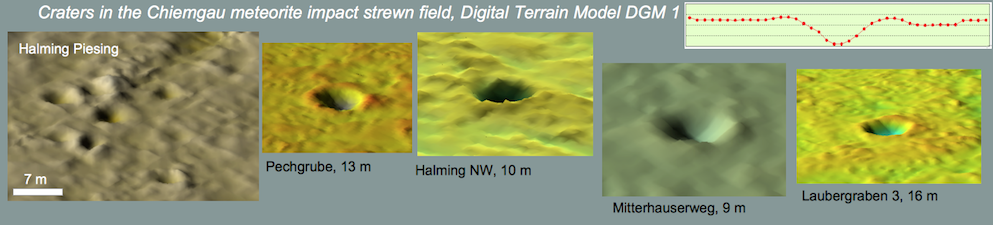

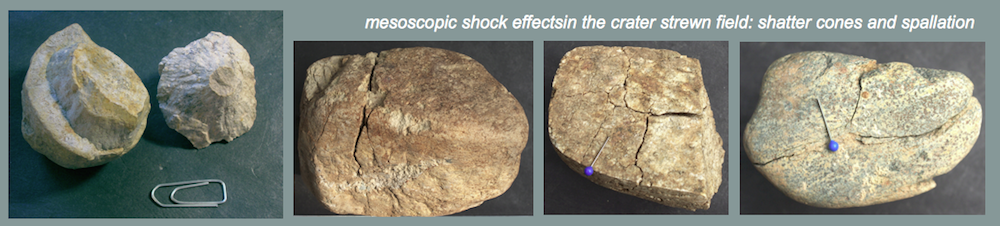

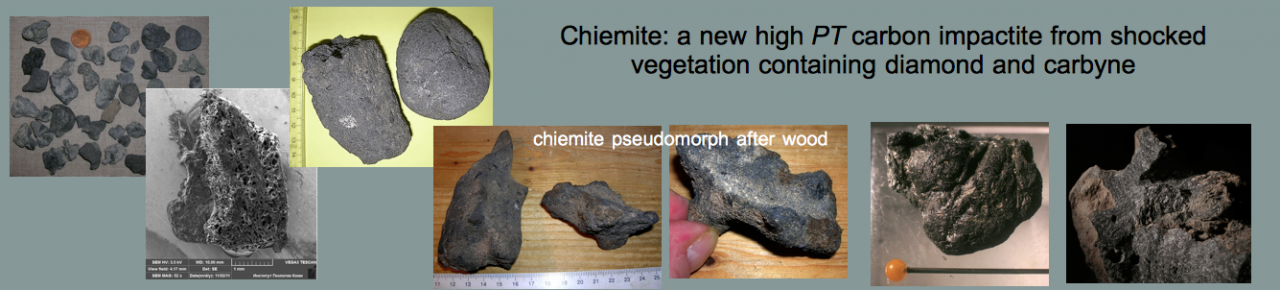

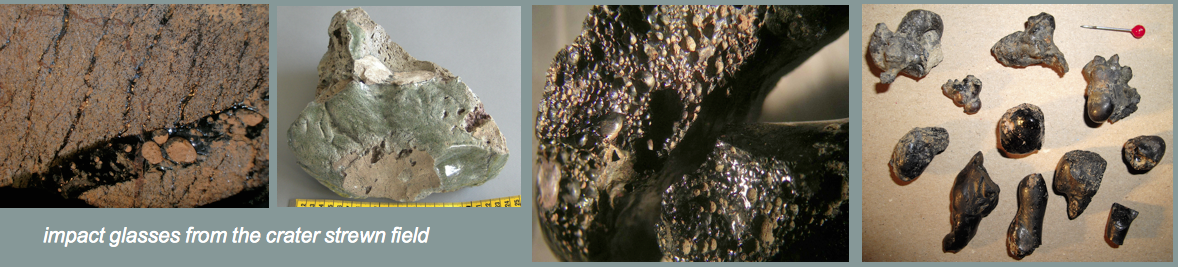

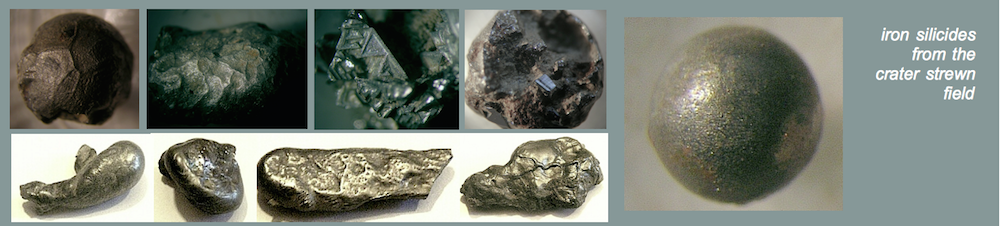

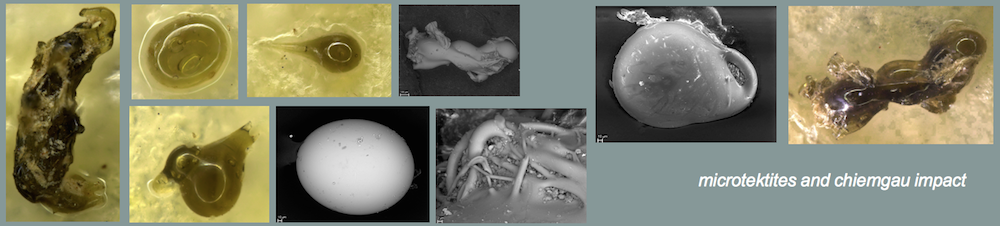

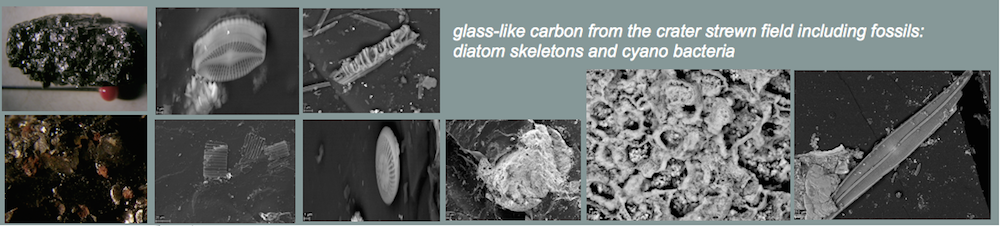

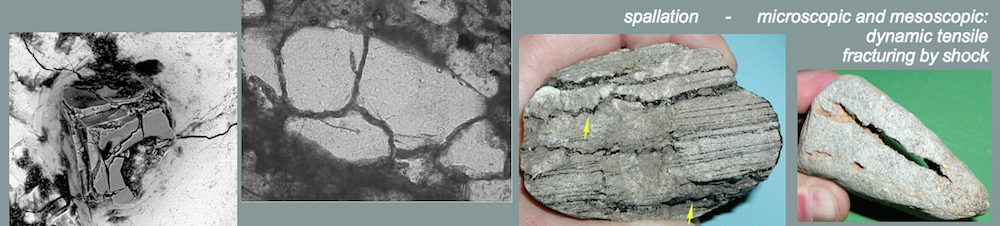

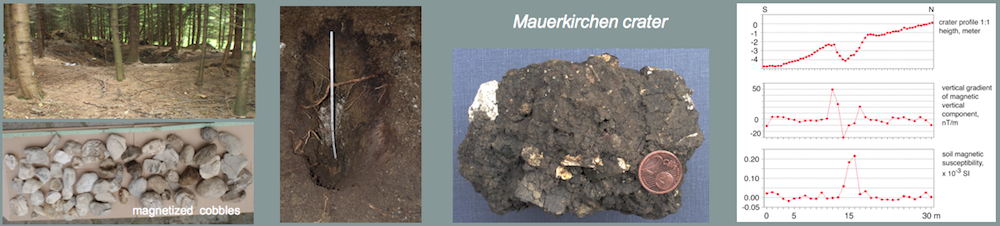

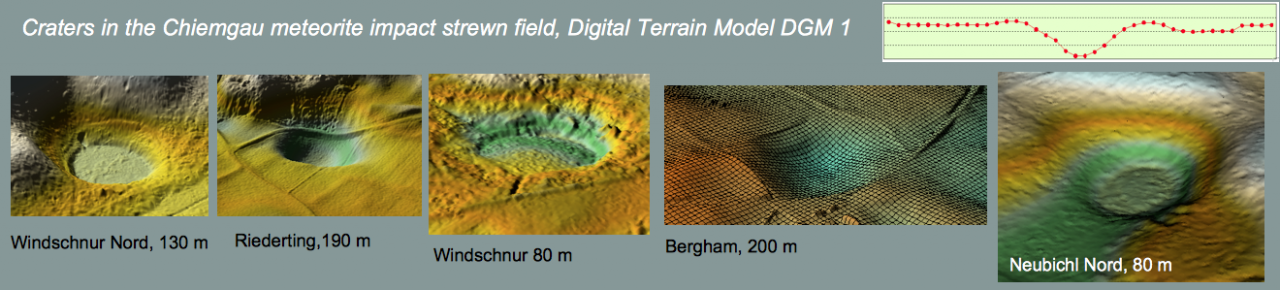

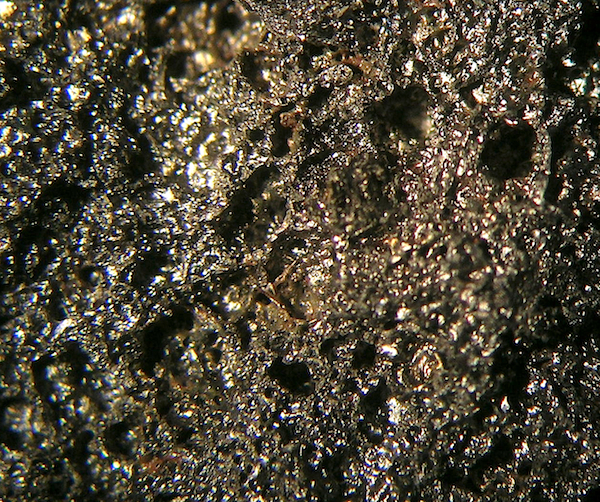

Abstract: – At the behest of the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation (BLfD) the archeological excavation at Stöttham near Lake Chiemsee, which exposed an intercalated geological layer with all evidence of a catastrophic deposition in a meteoritical impact event, was accompanied by a study performed by Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München [Science Center of Nutrition, Land Use and Environment, Technical University of Munich, at Weihenstephan]. In the now published article the exposure is most widely described and interpreted from a geomorphological and soil science perspective while the unambiguous impact features implying the typical heavy rock deformations and shock metamorphism (shock effects) are completely ignored. Nevertheless, the authors conclude that there are not any indications of an impact event. Here, we remind of the progress of events, discuss the major shortcomings of Völkel et al.’s article, and conclude that it doesn’t meet scientific requirements. Continue reading “Chiemgau Impact – a new article: Jörg Völkel, Andrew Murray, Matthias Leopold, and Kerstin Hürkamp: Colluvial filling of a glacial bypass channel near the Chiemsee (Stöttham) and its function as geoarchive. – Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie (Annals of Geomorphology), 56(3), 371-386, 2012.”