When is a meteorite crater a meteorite crater?

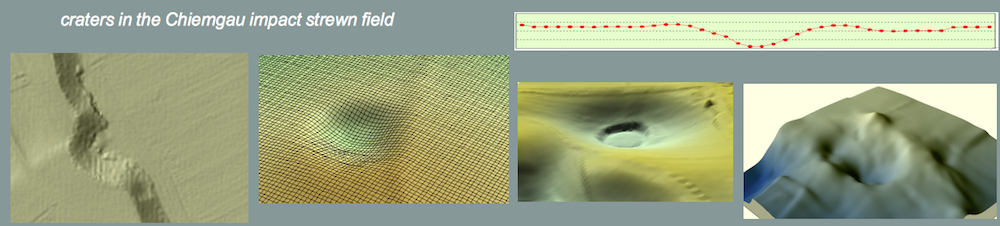

Image courtesy Google Earth

There are people believing this to be the case when a crater under discussion is accepted by a committee to be included in an official database like the Earth impact database of the New Brunswick university in Canada. There are other people being convinced a meteorite crater is a meteorite crater when there is clear scientific evidence for such an origin and who doubt that acommittee is qualified to decide on results of scientific research. This is the reason why different impact databases are revealing quite different numbers of established terrestrial meteorite craters (impact structures). Disregarding this fine distinction, there are quite a few criteria (e.g., morphological, geological, geophysical, mineralogic-petrographical, geochemical) as a base for the evaluation of a meteorite crater, and some of them are regarded as in proof of impact. In other words and to say it simpler: Having mapped basaltic rocks in the field, one will be convinced there is volcanism, and having mapped rocks displaying shock-metamorphic effects, one will be convinced there is a nearby impact site.

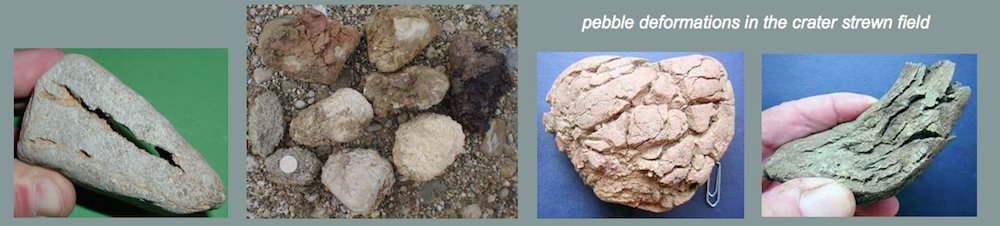

Impact criteria – compelling and less compelling – as compiled by Norton, O.R. (2002): The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Meteorites. – Cambridge University Press, pp. 291-299, and French, B.M. (1998): Traces of Catastrophe. A Handbook of Shock-Metamorphic Effects in Terrestrial Meteorite Impact Structures. Lunar and Planetary Institute, pp. 97-99 (download as a pdf file here), and others, are:

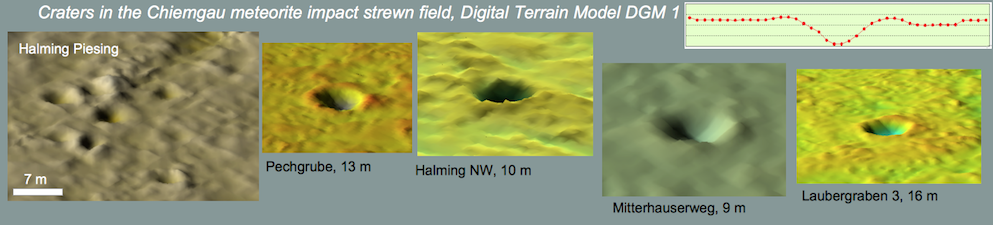

1. Morphology

Circular structures in general; depressions with raised rims or/and central uplifts; multi-ring structures: less meaningful because many other geological structures may show circular symmetries, and true impact structures may strongly deviate from such a shape.

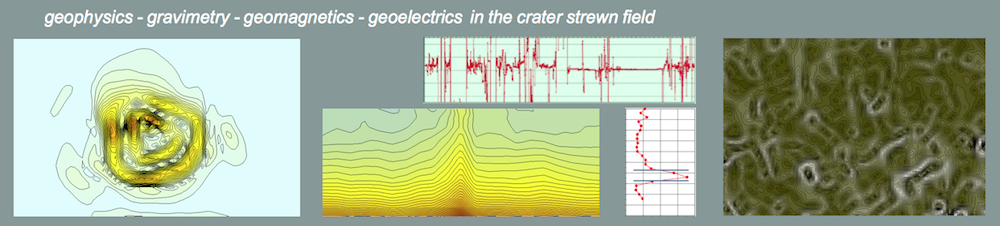

2. Geophysical anomalies

Many impact structures are closely related with characteristic gravity and magnetic anomalies, but reversely, measured anomalies in general don’t allow to deduce an impact event. Seismic reflection surveys may reveal the characteristic layering of buried impact structures.

3. Geologic evidence

Regularly found in and around impact structures: strong deformations, folding, faulting, fracturing; polymictic and monomictic breccias and dike breccias, megabreccias; high-pressure/short-term deformations of clasts in a soft matrix; rocks looking like volcanic or magmatic rocks; layers of exotic material.

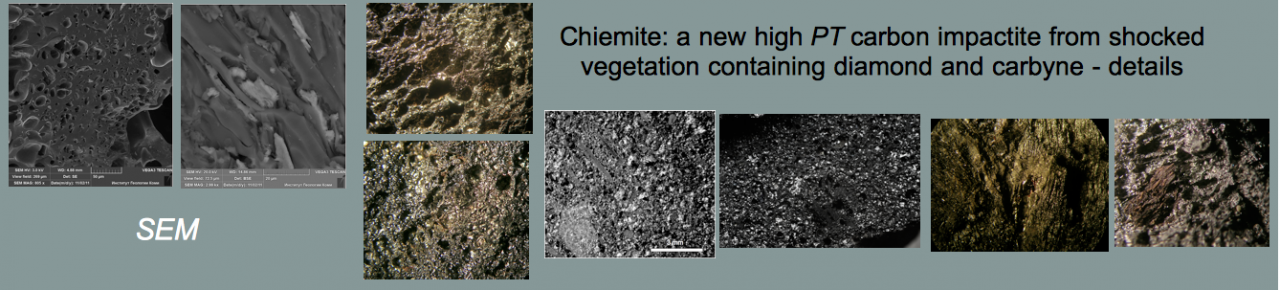

4. High-temperature evidence

Melt rocks, natural glasses, breccias with melt rock fragments and glasses

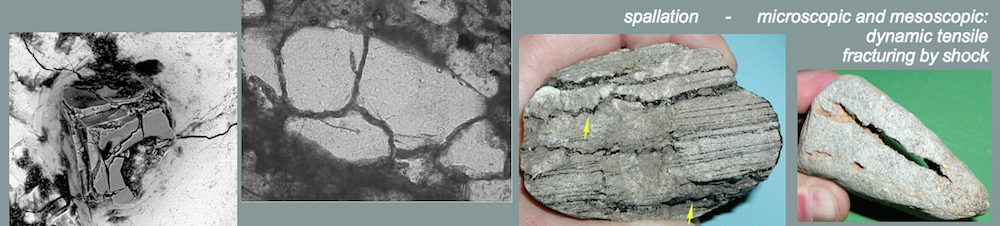

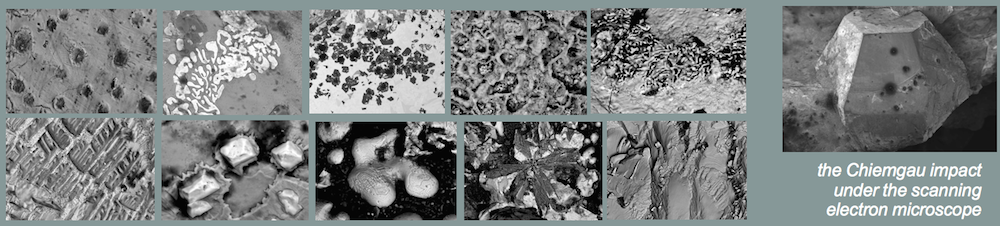

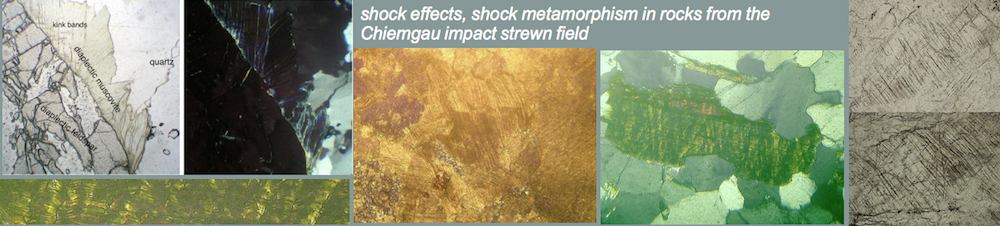

5. High-pressure evidence – shock metamorphism

Planar deformation features (PDFs) in quartz, feldspar and other minerals, planar fractures (PFs) in quartz, diaplectic quartz and feldspar crystals, diaplectic glass; multiple sets of intense kink banding in mica, multiple sets of microtwinning in calcite. Kink banding in mica and PFs in quartz are also known from very strong tectonic deformation.

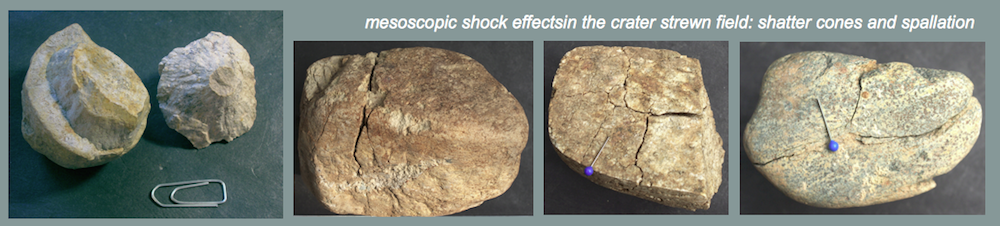

6. Shatter cones

Shatter cones, here in limestone from the Steinheim Basin impact structure and in an quartz-arenite from the Sudbury impact structure, are characteristic shock-induced conical fracture planes in all types of hard rocks. Shatter-cone fracture planes show typical “horse-tail” fracture markings.

7. Special evidence

Occurrence of micro and/or nano-diamonds; accretionary lapilli, various kinds of spherules. – Spherules may be anthropogenic.

8. Meteorite fragments

In larger meteorite craters in most cases completely absent because of vaporization of the projectile upon impact. Microscopic geochemical signature of the impactor is possible. Meteorite fragments are in general found in and around young small craters. In the Macha crater strewn field (Yacutia), however, the largest particles assumed to be meteoritic are 1.2 mm-sized only.

9. Direct observation (historical record)

Apart from the observation of meteorite showers (e.g., Sikhote Alin) impacts to have formed a meteorite crater have not been passed on. Geomyths may be interpreted as document of observed impacts.

According to current understanding, points 5. shock metamorphism, 6. shatter cones, 8. meteorite fragments, and 9. direct observation are each one by itself accepted as a confirmation of an impact event.

The criteria 1. – 9. applied to

the Chiemgau crater strewn field

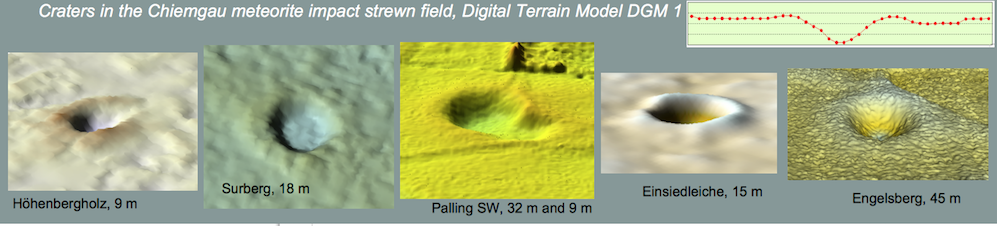

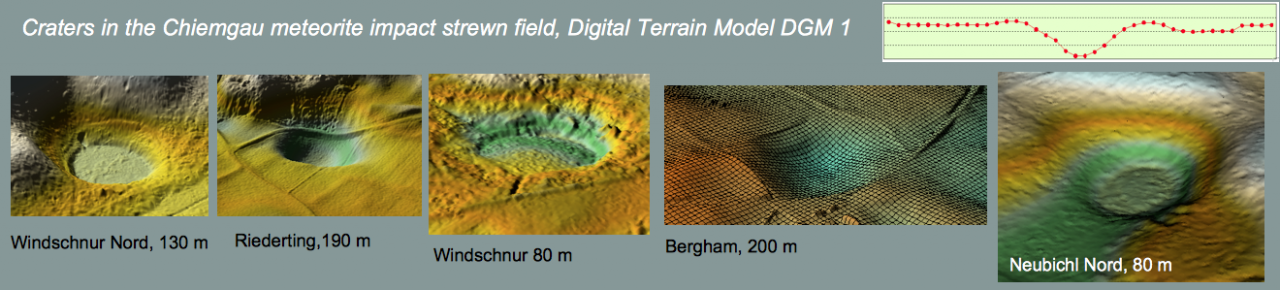

1. Morphology – yes

Numerous circularly shaped craters with raised rims

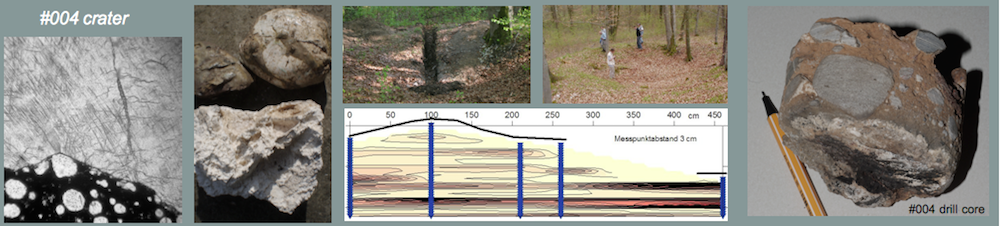

The 11 m-diameter crater no. 004 in the Chiemgau impact strewn field. Note the distinct raised rim.

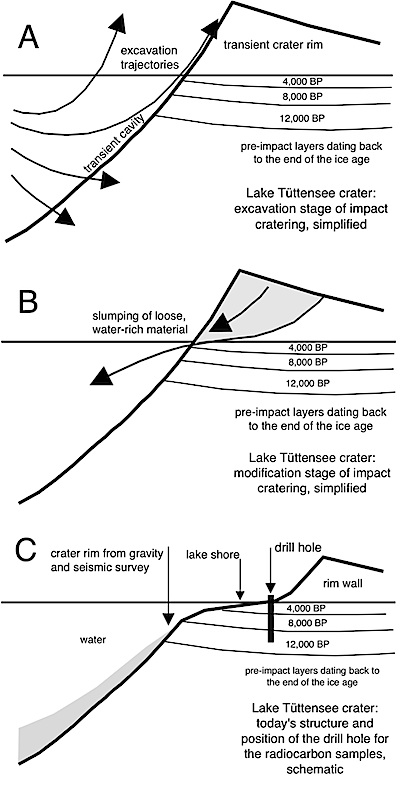

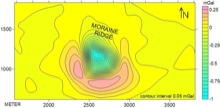

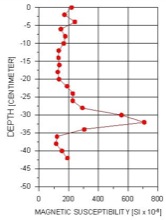

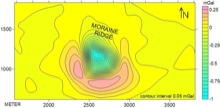

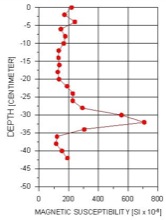

2. Geophysical anomalies – yes

– Gravity negative anomaly of the Lake Tüttensee crater surrounded by a conspicuous zone of relatively positive anomalies

– A distinct horizon of strongly enhanced soil magnetic susceptibility in the strewn field.

Gravity survey (Bouguer residual anomaly) of the Lake Tüttensee crater

Anomalous soil magnetic susceptibility profile near the Lake Tüttensee crater

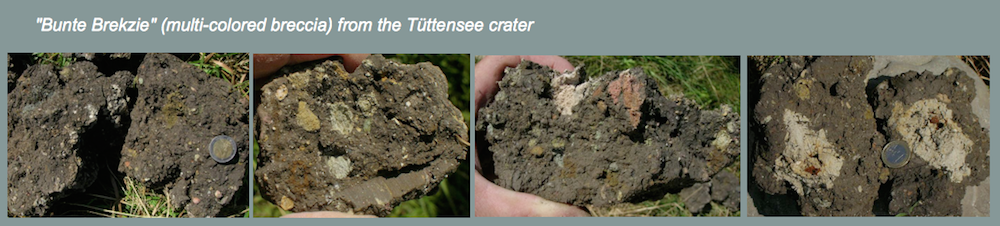

3. Geologic evidence – yes, multiple

Multicolored polymictic impact breccia from the Lake Tüttensee crater ejecta layer.

Highly fractured however coherent carbonate and silicate clasts from the Lake Tüttensee crater ejecta layer: evidence of high-pressure/short-term deformation.

Highly fractured and squeezed however coherent quartzite cobble from the Lake Tüttensee crater rim wall: evidence of high-pressure/short-term deformation

The Stöttham exotic impact layer (arrow)

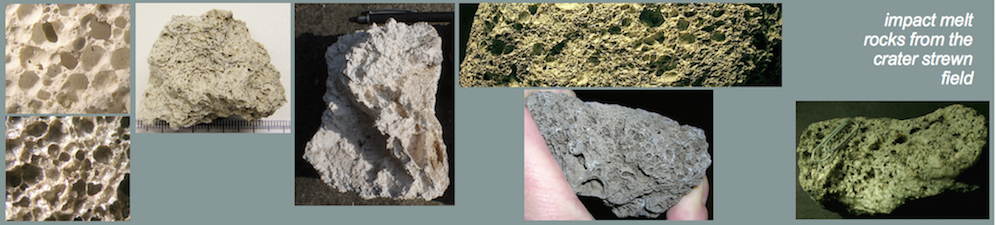

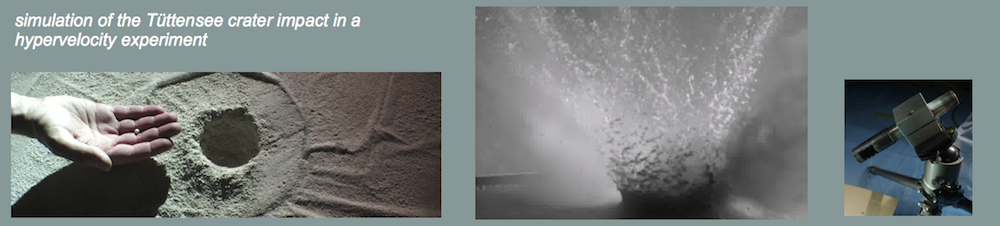

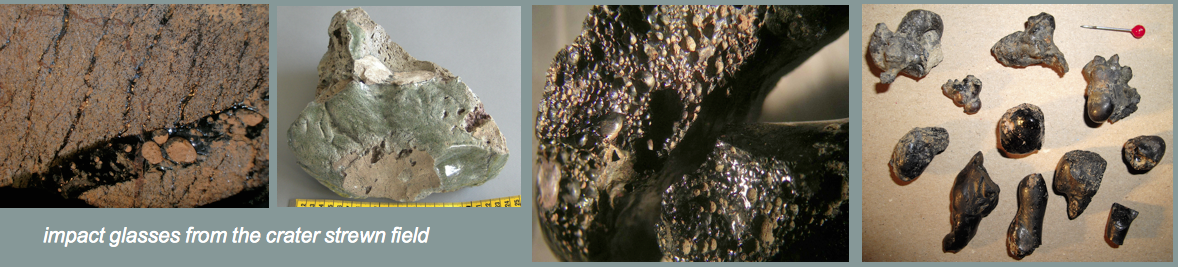

4. High-temperature evidence – yes

Pumice-like impact melt rock from the Lake Tüttensee crater.

Two glass-coated cobbles welded by cindery glass from crater no. 004

Sawed surface of a silicate cobble from crater no. 004. Extremely vesicular and fissured rock where, except for quartz, all minerals are more or less transformed to glass giving the dark color to the rock. The widely open fissures may result from shock spallation.

5. Shock metamorphism – yes

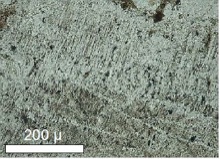

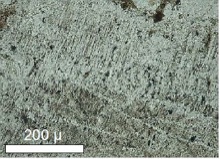

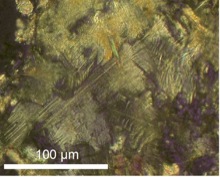

“Toasted” quartz with multiple sets of PDFs in quartz; photomicrograph, crossed polarizers, quartzite clast from the Lake Tüttensee crater rim wall. “Toasted” quartz is a common feature in shocked grains and is explained by tiny fluid inclusions. – For comparison to the right: toasted quartz with PDFs from the Popigai impact structure, Russia

.

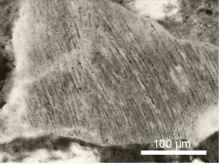

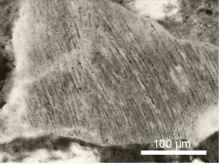

Two sets of planar deformation features (PDFs) in quartz; photomicrograph, crossed polarizers, 1.5 mm field width; quartzite clast from the Chiemgau impact 004 crater. The slightly curved PDFs must not irritate: Although there are authors, e.g. Reimold & Koeberl (2000), who claim bent PDFs are of non-impact origin, the example of the Popigai bent PDFs in the above image and many other examples from various impact structures show the verdict of Reimold & Koeberl is not tenable

.

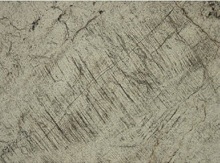

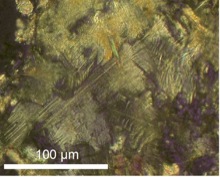

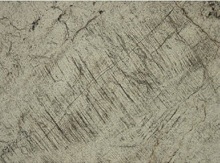

Twin lamellae and multiple sets of PDFs in feldspar. Photomicrograph, crossed polarizers; impact melt rock from the Lake Tüttensee crater.

6. Shatter cones – yes

Two shatter cones in counter position in a fine-grained sandstone from the Lake Tüttensee crater.

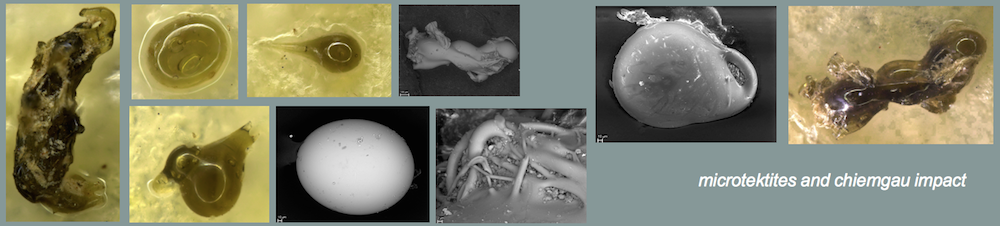

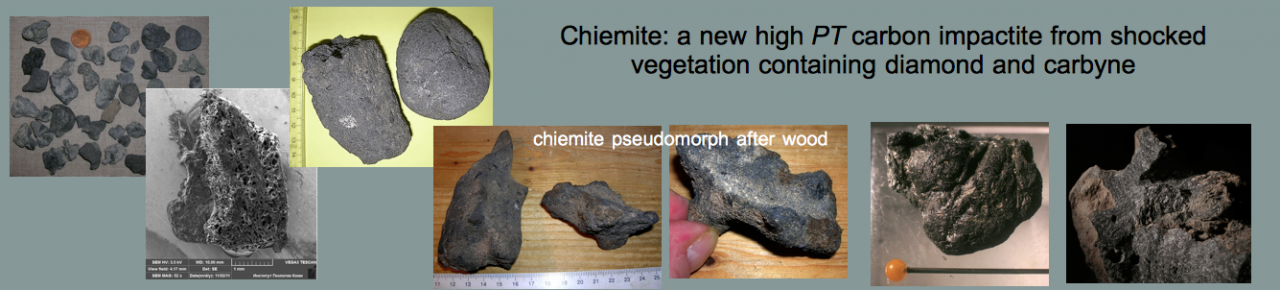

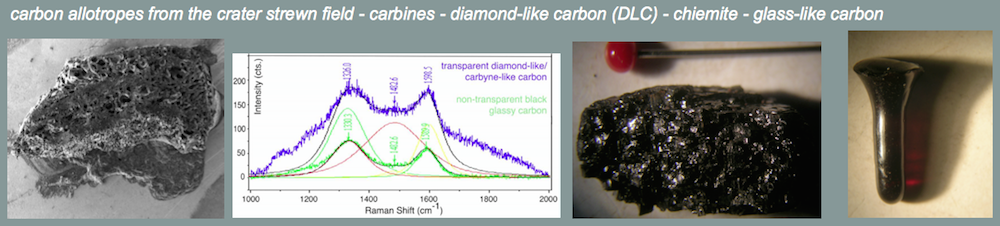

7. Special evidence – yes

Nanodiamonds – yes

Article

Rösler W., Hoffmann V., Raeymaekers, B., Schryvers, D. and Popp, J. (2005) Diamonds in carbon spherules –evidence for a cosmic impact? (http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/metsoc2005/pdf/5114.pdf; 7.5.2006).

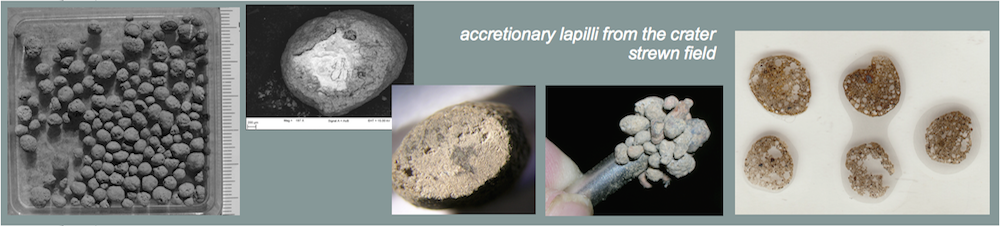

Accretionary lapilli – yes

Accretionary lapilli (to the right with a fragmental metallic core) from the Chiemgau impact strewn field. Lapilli diameters about 4 – 5 mm. Accretionary lapilli are normally known from volcanism but have been shown to occur also in impact structures where they have been formed in the impact explosion cloud.

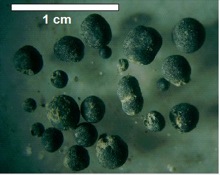

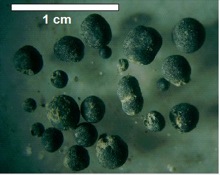

Spherules – yes

2 mm-diameter broken vesicular glass spherule; Stöttham impact layer.

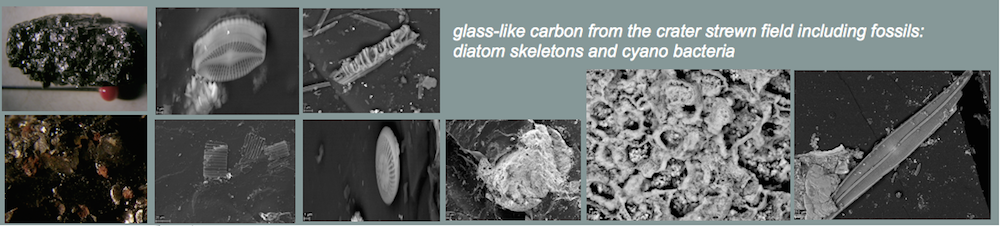

Carbon spherules from various sites in the Chiemgau impact strewn field. Also see Yang, Z.Q. et al., 2008: TEM and Raman characterization of diamond micro- and nanostructures in carbon spherules from upper soils. – Diamond and Related Materials 17/6: 937-943.

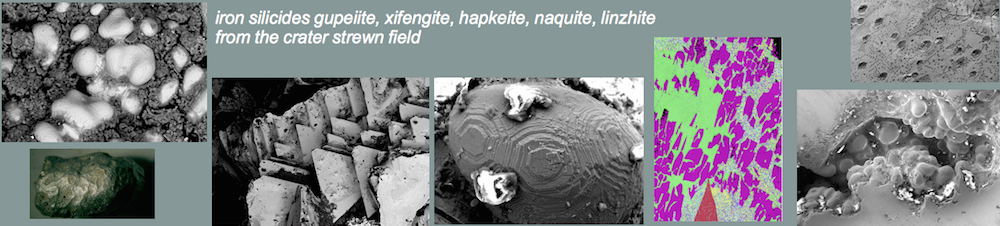

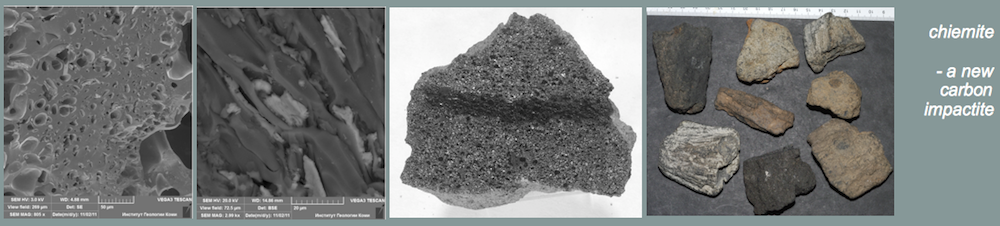

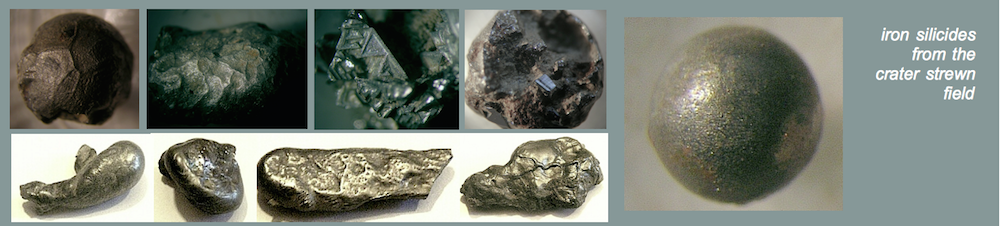

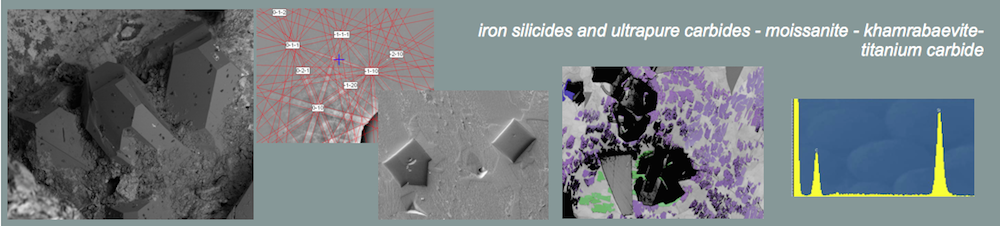

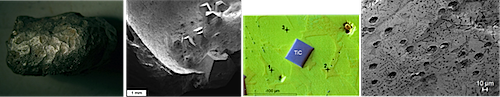

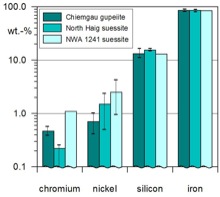

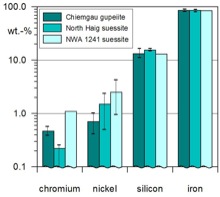

8. Meteorite fragments – probably yes

Exotic material like iron silicides gupeiite and xifengite, carbides like titanium carbide and silicon carbide moissanite strongly point to extraterrestrial origin.

SEM image of moissanite crystals in iron silicide matrix. Sample from the Chiemgau meteorite crater strewn field.

Comparison of analyses of Chiemgau gupeiite and meteoritic suessite

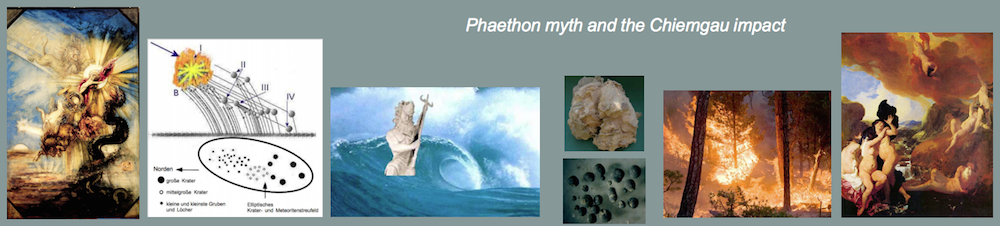

9. Direct observation (historical record) – possibly yes

Peter Paul Rubens: The fall of Phaeton, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Article

Rappenglück, B. and Rappenglück, M., 2006: Does the myth of Phaethon reflect an impact? – Revising the fall of Phaethon and considering a possible relation to the Chiemgau Impact. – Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 6/3 (2006), 101-109.